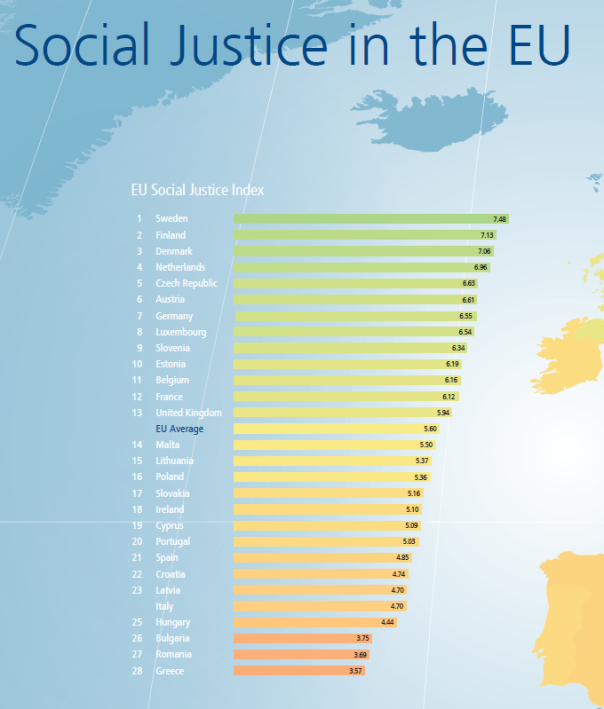

A report that found that Greece ranks last among the EU’s 28 members in terms of social justice has urged the government to do more to concentrate its efforts not only on returning to a stable path of growth, but also on improving participation opportunities for a broader portion of the population.

Published by the German Bertelsmann Foundation, the report (pdf) said while Greece, along with Spain and Italy, has a comparably high GDP per capita, it performed “far worse” in the social justice index rankings, which measures performance in poverty prevention, access to education, access to the labour market, social cohesion, non-discrimination, health and intergenerational equity.

“Greece is at the bottom of the ranking with a youth unemployment rate of nearly 60%, a rapid increase in the risk of poverty, particularly among children and youth, a health care system badly undermined by austerity measures, discrimination against minorities as a result of strengthened radical political forces, and an enormous mountain of debt that represents a mortgage on the future of coming generations,” the report found.

“The resulting diminution of prospects for broad swathes of society represents a significant danger to the country’s political and social stability. These developments illustrate that the cuts induced by the crisis are not administered in a balanced way throughout the population,” it noted.

Of the six indicators measured in the report, Greece came last in four: access to education, access to the labour market, social cohesion and non-discrimination and intergenerational equity. In health, it was ranked 24th and in poverty prevention 25th out of 28.

It said that from a social justice perspective, “it is particularly important that to the extent possible, a student’s socioeconomic background has no effect on his or her educational success”, noting that Finland and Estonia were the most successful EU countries in this regard.

The report also said that “given the lack of prospects for young people” in Spain and Greece due to the high youth unemployment rate, “this must be regarded as a lost generation”. Some 31.6% of people between the ages of 20 and 24 are so-called NEETs, meaning they are neither in employment or participating in training or further-education programmes. “In Greece, the NEET rate nearly doubled between 2008 and 2013,” it found.

In terms of equality, the study found that Greece, along with Croatia, Hungary, Malta, Romania and Slovakia, shows the most significant deficiencies in the EU with respect to protection from discrimination. “In these countries, minority elements occasionally face systematic discrimination,” the report said.

Pointing out that generational justice keeps families and senior citizens alike in focus and seeks a balance between the interests of the young and old, the report said that Greece and Italy displayed the “the greatest shortcomings with regard to intergenerational justice”.

It urged that while budgetary consolidation must be prioritised in the interest of future generations, ,”to the greatest degree possible, care should be taken in the course of this fiscal consolidation to maintain investment in policy areas that are particularly relevant to the future”.

The Bertelsmann Foundation said that the findings underlined the dangers facing the EU project.

“The growing social divide between member states and between the generations can lead to tensions and a considerable loss of trust. Should the social imbalance last for long or increase even more, the future of the European integration project will be threatened,” warned Dr Jörg Dräger, from the foundation.

Calling for social justice to take a place at the centre of the European political agenda, the foundation noted that “EU’s own efforts to create a more socially just Europe, however, have remained rather feeble, at least as perceived by the general public”.

Although that has to be set against the recent years of near-apocalyptic “austerity”, which I doubt any other European country could have coped with as “well” as Greece. Despite the recession, soaring youth unemployment and Chrysi Avgi still active in my community, Greece remains one of the most classless, resilient and welcoming cultures in the world.

Which is why I’m here, their hospitality willing, yia panta…

Reblogged this on ΕΝΙΑΙΟ ΜΕΤΩΠΟ ΠΑΙΔΕΙΑΣ.

John Gill makes a good point: the social cohesion of “old fashioned” societies like Greece, with emphasis on family, neighbourhood, church (unfashionable as this may be, the church has stepped up to the plate massively in terms of social programs) has literally ‘saved’ the country – plus survivable weather & the 1-2€ souvlaki. I could not imagine the more atomised north doing as well.

That said, the state has become a predator on the Greek people (with the EU/IMF behind), reducing democratic access, inflating the powers of the state and police to control the population, throwing out successive parts of the constitution and strongly supporting the rich while suctioning out the savings of the poor: this is not the template of a healthy democracy, or of a healthy country – nor was it the promise of the “EU”. Furthermore we watch as the government aids and abets the further enrichment of our mafiosi oligarchs through TAIPED, special legislative favours, ‘competitions’ with one candidate, ‘blind eyes’ etc. Yes, huge fortunes are being made.

All in the name of shoring up bankrupt Deutsche Bank et al, and the abuse of power and refusal to assume their part of the responsibility on the part of Germany and other states who made irresponsible loans. Of course this process is not new – Greece’s unwilling contribution to the downhill trend in civilisation was to be denied debt restructuring early on, setting new lows.